Education is one of the most lasting casualties of wars, genocides, and invasions. Not only are schools and educational structures targeted and destroyed, but the escalation of violence puts students, teachers, school staff and the collective learning process at risk. A reality that has long been evident in territories riven by violence and oppression, and which has led analysts to speak of “scholasticides”.

Scholasticides : When Systemic Violences Target Knowledge Processes

The term “scholasticide,” coined by Oxford Professor Karma Nabulsi, refers to the systematic destruction of education aimed at undermining “the fundamental basis of the social order”. This concept was introduced in 2009 during Israel’s assault on the Gaza Strip and highlights a longstanding pattern of colonial attacks on Palestinian scholars, students, and educational institutions that dates back to the Nakba of 1948.

The term was recently used by United Nations experts to characterise the unprecedented violence in Gaza. They expressed serious concerns about the pattern of attacks against schools, universities, teachers and students that go beyond isolated offensives. Indeed, 90% of all school buildings have been damaged or destroyed in half a year, and the latest figures speak of 261 teachers killed and 1.4 million people using schools as shelters.

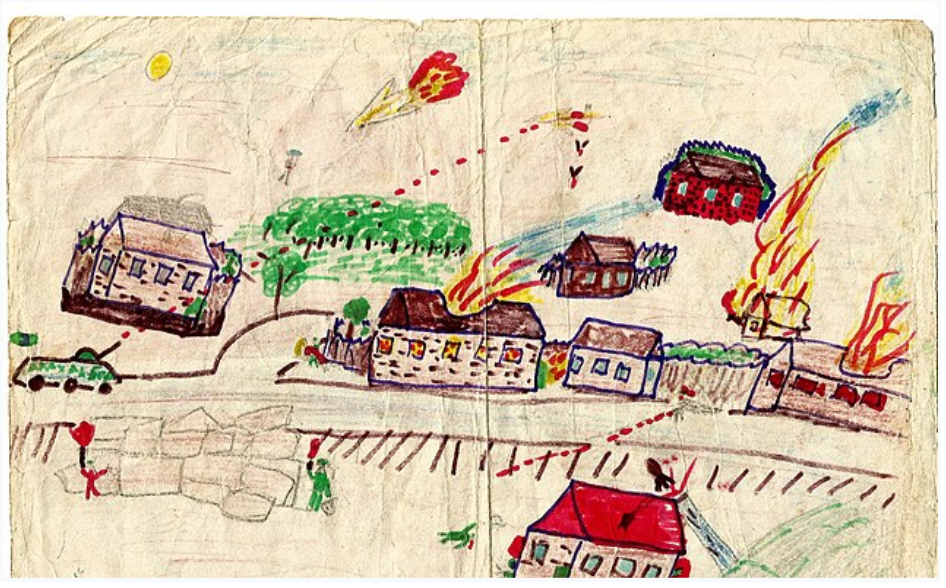

A War on Children and Their Future

In Gaza alone, since the 7 October attacks in which 33 Israeli children were killed by Hamas forces, the estimated number of Palestinian children killed by the Israeli army increases day by day. At the time of writing, international organisations speak of over 14,000 child casualties (of which 7,779 have been identified). For the survivors, the destruction of schools endangers the education, childhood, and future years of an entire generation long after the violence has subsided. In addition, the enduring psychological trauma faced by children in the region is deeply concerning. A number of violations of children and human rights are at play here including the right to life and security (UDHR Article 3, CRC Article 6), the right to education (UDHR Article 26, CRC Article 28), and the right to health and well-being (UDHR Article 25, CRC Article 24) of children.

In Ukraine, such violations have also occurred, with over 1,957 children killed or injured and over 3,790 educational facilities damaged or destroyed since the Russian invasion in February 2022. According to UNICEF, this has severely interrupted access to education for millions of children, with many of them being forced to spend up to 5,000 hours – or the equivalent to nearly 7 months – sheltering underground instead of being with their peers playing, learning and enjoying their childhood. It also means that half of all 13-15-year-olds have trouble sleeping, and 1 in 5 have intrusive thoughts and flashbacks, which are “typical manifestations of post-traumatic stress disorder.”

In Sudan, the deep rooted civil war is resulting in the destruction of children and their schools as crucial safety structures. 19 million children have so far been forced out of school since April 2023, and at least 89 schools across seven federated states are being used as shelters for the displaced, urging the United Nations to qualify the country at “the brink of becoming home to the worst education crisis in the world.”

Education’s Role in Preserving Safety, Freedom, Justice, and Hope

The long-term repercussions that war, genocides, and invasions can have on the education realm have led education representatives to rise up against the violence threatening the bodies, minds, and histories of people. Furthermore, studies indicate that effective reconstruction and peacebuilding must address significant negative impacts of war on education, including displacement, child recruitment, profit-driven education, mental health issues, and unpaid teacher salaries.

Most importantly, this must be coupled with the recognition of education’s crucial role in fostering freedom, hope, resistance, and peace, rather than imposing militarised perspectives. In particular, we should emphasise the critical role of democratic education in fostering a sense of cohesion, unity, and democratic values in children. By instilling these principles from a young age, we can help ensure that, as adults, they will be more inclined to reject violence and oppression in their visible and less visible forms.

Moreover, collectively educating ourselves on the root causes of these conflicts, including their historical legacies, colonial power dynamics, and intricate international and geopolitical entanglements, is crucial. Equally important is addressing Europe’s responsibility for the educational destruction occurring in these countries. What can Europe do to raise awareness about what’s happening? What concrete actions can be taken to address the urgent needs of the civilian population and to avoid further suffering? Only by questioning and understanding the dynamics that forge and fuel war, can we move towards justice, restoration, and lasting peace.