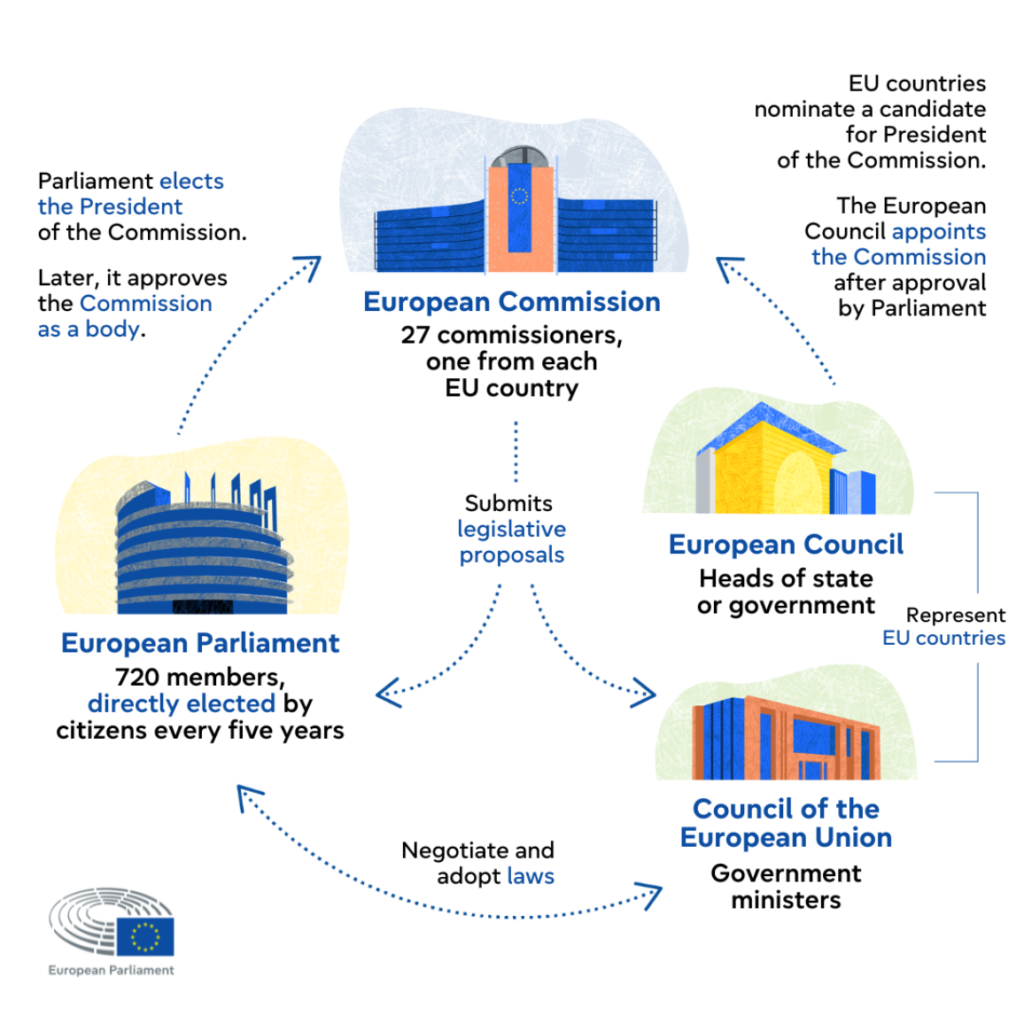

National legislations, promoting or restricting cutting-edge education, can be highly inspired by laws passed at the EU-level. These laws are shaped by political representatives that we elect every 5 years, and so does the strategic orientation of the EU change. But what does it actually mean? And how does it work?

European legislations, which are negotiated between three EU institutions (the EU Commission, the EU Parliament and the Council of the European Union) pave the way for national legislations. This can be done either through EU recommendations to national governments, as it is the case in the field of education, or through legal translations of EU policies into national law.

The European Commission has the initiative of proposing such laws, in most cases. The legislative proposal is then negotiated between the European Parliament, directly elected by the European citizens every five years, as this happened last June, and the Council of the European Union, representing Member States through national ministers. This is called the Institutional Triangle of the European Union.

The election of the European Parliament: the voice of EU citizens

Election of the Members of European Parliament

During EU elections, we first elect nationally our representatives to the European Parliament, for the next five years, called Members of the European Parliament (MEPs). The number of representatives per country is calculated before each EU election, and follows the size of the population of member states, with a minimum of 6 seats and a maximum of 96 seats per country. It embraces the idea of representing European citizens fairly, which means a country with a higher number of European citizens should be granted higher political power, therefore a higher number of MEPs. Germany, France, Italy, Spain and Poland, have the highest political power in that regard, with respectively 96, 81, 76, 61 and 53 seats in the European Parliament.

Once elected to the European Parliament, national political divides do not stop. Instead, MEPs gather under similar political lines, in European Political Parties. The number of seats attributed per European Political Party also matters in the legislative process. To be caricatural, a European Parliament with a left majority could see higher slices of the European budget going to social investments, such as education, while a European Parliament with a right majority would see more investments in market competition or security.

Committees in the European Parliament

To facilitate the handling of legislative procedures, the European Parliament is divided into Committees, such as the Committee on Culture and Education (CULT), which will discuss and propose amendments to the legislative proposal of the European Commission. After amendments, it will then be voted by all the MEPs in the plenary of the European Parliament, in Strasbourg. Each committee is made up of a Chair, leading each session and overseeing the completion of the committee’s work, and of 4 Vice-Chairs, to replace the Chair in case of absence.

After the European elections, European Political Parties will negotiate to identify which number of strategic positions would be given to which political parties, taking into account the results of the European Elections, with political alliances sometimes privileging some parties over others. The political representation of the MEPs sitting in at the head of committees can therefore influence the direction of legislative amendments, before the final vote in plenary.

The election of the European Commission

After the election of the EU Parliament, comes the nomination of the President of the European Commission, which, we will remind here, has the monopoly of legislative proposals. The EU Commission is the only EU body, putting aside exception cases, that can propose an EU law, which will then be negotiated. The EU commission therefore has great legislative power, proposing Political Guidelines for the EU for the new mandate, although it has to follow the agenda of the European Council – a final EU institution made of heads of governments and setting the strategic orientation of the EU. Each European Political Party can nominate a candidate to the position of President of the European Commission. The candidates are finally voted by the newly elected EU Parliament, and approved by the European Council.

The European Commission is divided into 27 Directorate-Generals (DGs), specialised on one field of action at the EU level. There is, for instance, a DG focusing on education, youth, sport and culture, called DG EAC. Although being made majoritarily of politically-neutral European bureaucrats, these Directorate-Generals are headed by an elected figure, called Commissioner. After each European election, each member state has to propose a list of candidates to the position of Commissioner. While they are supposed to remain politically neutral, the European journal Euractiv, has underlined how in the past, some have “played power games in their files.” In the past mandate, the former President of the European Commission, Ursula von Der Leyen, had asked for two proposals for nomination per member states, of a woman and a man, to ensure gender parity. This year, Member states had until the 30th of August to nominate their candidate.

Political negotiations then pursue between European Political Groups and Member States, notably regarding the national results of the European Elections, as to identify the candidates to nominate as well as which DG they could be heading. Some DGs could bring more political power than others, that is notably the case of the DG focusing on the budget of the European Union.

After proposal from the Member States, The President of the European Commission officially nominates the Commissioners, and their respective DG, who will each have to present themselves to the newly elected European Parliament and be voted upon. A nominated candidate can therefore be refused by the European Parliament, leading new discussions and nominations.

Following these changes at the European level, new legislative proposals are started by the European Commission, negotiated by the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. But these political changes can greatly affect our ambitions as a collective, for the best or for the worst… And more precisely for 5 years. It is therefore crucial, for NGOs working in education and in children’s rights, to monitor the state of political developments at the EU-level, as it can equally lead to an increase or a cut in budget for education, less or more legislative restraints, high or low interest in children’s rights (…) which can in turn promote progress or regress in the EU.